Rapid global urbanisation has truly transformed urban areas into major hubs, where most of the living, production and consumption occurs. In 2018, more than 55% of the global population resided in urban settlements with projections of urban dwellers to account for 60% of the global population by 2030. In addition, there is also a projected 2.5 billion increase in the global urban population by 2050, implying that 2/3 of people will live in urban areas. More pertinently, it is estimated that 90% of this increase will take place in Asia and Africa (UN DESA, 2018).

From a variety of interdisciplinary perspectives, these growing cities are open systems that are reliant on continual supplies of resources to function and to best serve their residents. Inherently, food is also inextricably linked to new and expanding urban agglomerations with approximately 80% of all food produced globally destined for consumption in urban spaces (Bailey, 2011).

So, why is it important to analyse the effects of urbanisation on urban food systems?

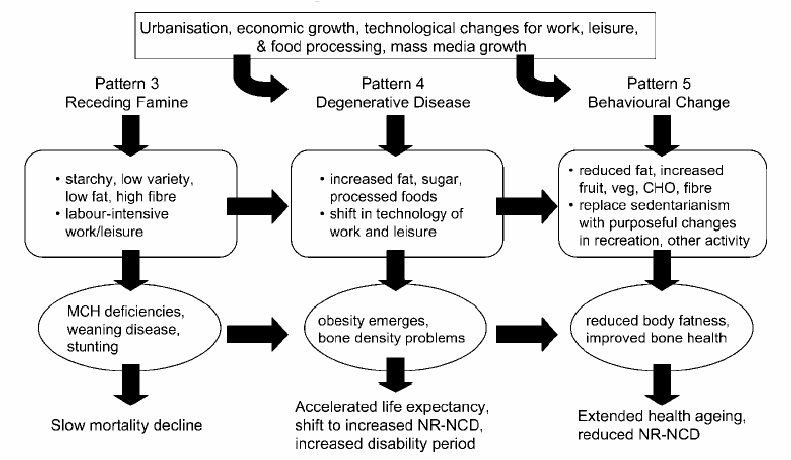

With an improvement in living standards, the dietary structure generally shifts towards a decrease in the consumption of coarse grains, staple cereals, and pulses to an increase in consumption of oils, meat, refined sugar and processed foods, and in some areas either an increase or a decrease in the consumption of fruits and vegetables, a phenomenon referred to as a “nutrition transition” (Popkin, 1998).

These changes are happening globally, however, the most rapid changes are occurring in the urban regions in the Global South. Changes in food supplies resulting from globalisation and economic expansion open the opportunity to address under-nutrition through the introduction of new goods in places in the Global South that have traditionally largely depended on locally grown produce, as these new items may increase dietary diversity and food stability. On the other hand, many of these newly introduced products are non-perishable, pre-prepared with low-nutritional value and high fat, sugar and salt content; promoting malnutrition in the form of obesity (Cunningham et al., 2021).

A major point of interest is that as countries develop economically the prevalence of overweight and obesity rates appear to increase amongst the poorest while the wealthiest cohorts remain largely unchanged. In brief, urban dwellers are particularly susceptible to these nutrition transition dietary transformations. This can be caused by several factors such as the affordability of ultra-processed foods such, poor infrastructure that hinders the timely transport of perishable food items or consumer-orientated food safety concerns. In the case of Hanoi, Vietnam consumer purchasing habits are heavily influenced by personal beliefs about what constitutes a ‘safe’ retail outlet, a nudge from the younger generation to eat more ‘westernised’ food such as fried chicken, and the growing desire to consume more animal-sourced foods (Wertheim-Heck & Raneri, 2019).

Bringing attention to the fact that similarly to the reality of famines that a lack of food is rarely the issue but a lack of access to it – the same can be said for the number of deficient diets seen in many rural areas. The double or triple burden of malnutrition is not simply the outcome of personal choices but a failure of urban food systems to provide healthy sustainable food as an accessible and affordable choice for all.

Therefore, as these dietary transformations are being felt globally is it not only of major importance to monitor these alterations closely, ideally using standardised frameworks and methodologies, but to simultaneously promote sustainable, inclusive and equitable urban food systems to best tackle the mounting threats of urban malnutrition.

References:

Bailey, R. (2011)Growing a better future: food justice in a resource-constrained world.

Cunningham, S. A., Shaikh, N. I., Datar, A., Chernishkin, A. E., & Patil, S. S. (2021). Food subsidies, nutrition transition, and dietary patterns in a remote Indian district. Global Food Security, 29, 100506.

Popkin, B. M. (2002). An overview on the nutrition transition and its health implications: the Bellagio meeting. Public health nutrition, 5(1A), 93-103.

Popkin, B. M. (1998). The nutrition transition and its health implications in lower-income countries. Public health nutrition, 1(1), 5-21.

UN- DESA (2018). Revision of World Urbanization Prospects

Wertheim-Heck, S. C., & Raneri, J. E. (2019). A cross-disciplinary mixed-method approach to understand how food retail environment transformations influence food choice and intake among the urban poor: experiences from Vietnam. Appetite, 142, 104370.